At least 1,000 years before the Greek mathematician Pythagoras looked at a right angled triangle and worked out that the square of the longest side is always equal to the sum of the squares of the other two, an unknown Babylonian genius took a clay tablet and a reed pen and marked out not just the same theorem, but a series of trigonometry tables which scientists claim are more accurate than any available today.

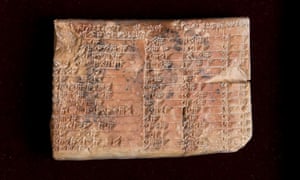

The 3,700-year-old broken clay tablet survives in the collections of Columbia University, and scientists now believe they have cracked its secrets.

The team from the University of New South Wales in Sydney believe that the four columns and 15 rows of cuneiform – wedge shaped indentations made in the wet clay – represent the world’s oldest and most accurate working trigonometric table, a working tool which could have been used in surveying, and in calculating how to construct temples, palaces and pyramids.

The fabled sophistication of Babylonian architecture and engineering is borne out by excavation. The Hanging Gardens of Babylon, believed by some archaeologists to have been a planted step pyramid with a complex artificial watering system, was written of by Greek historians as one of the seven wonders of the ancient world.

Daniel Mansfield, of the university’s school of mathematics and statistics, described the tablet which may unlock some of their methods as “a fascinating mathematical work that demonstrates undoubted genius” – with potential modern application because the base 60 used in calculations by the Babylonians permitted many more accurate fractions than the contemporary base 10.

Read more: Mathematical secrets of ancient tablet unlocked after nearly a century of study